Rethinking Nubian identity in Egypt during the 3rd millennium BCE

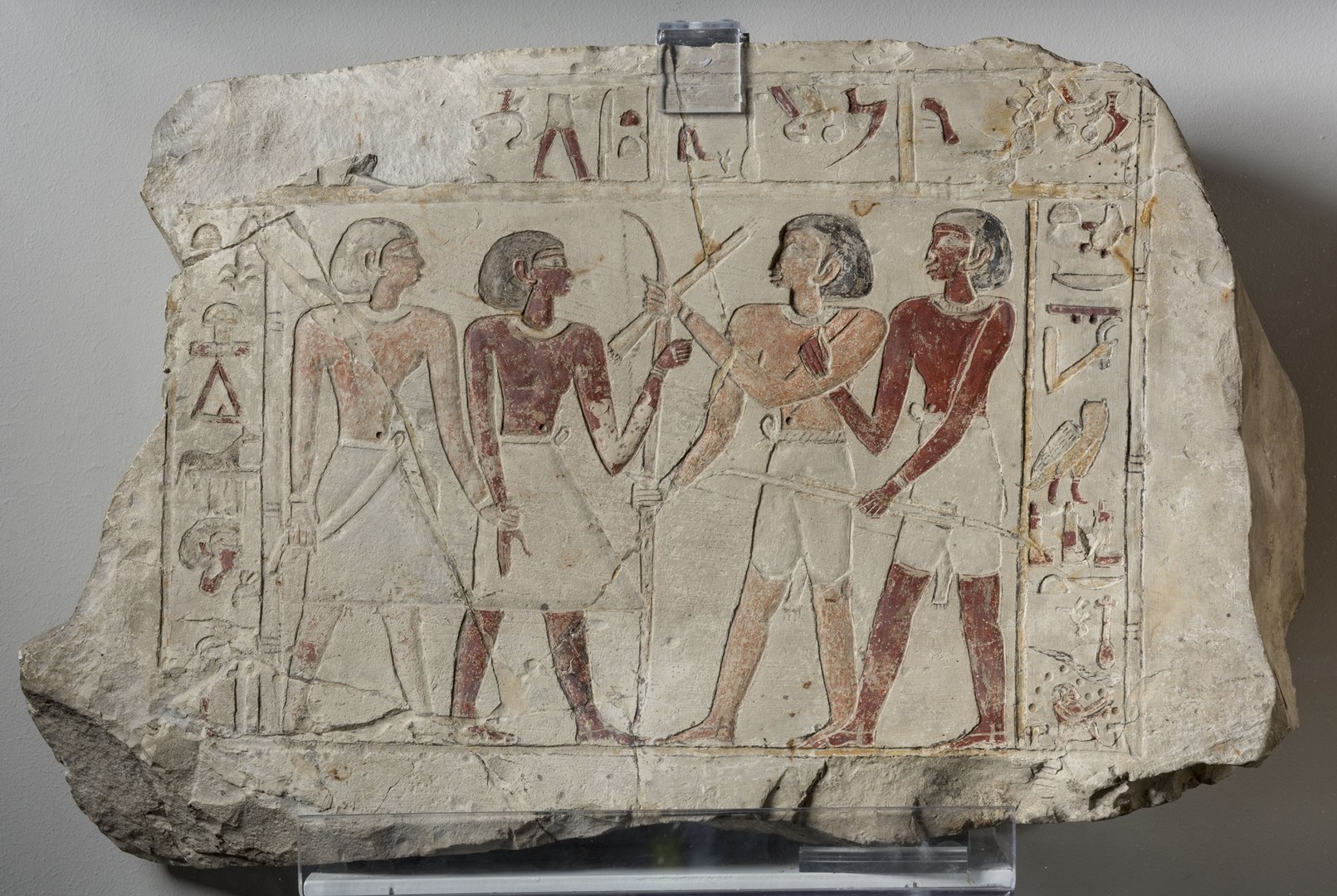

For convenience, the bearers of the archaeological C-group culture are equated here with “Nubians”. However, this should not be accepted without any objections: mostly because there is no commonly accepted definition of ethnicity, especially when dealing with archaeological data. For this project a sort of intuitive approach will be adopted at the beginning and possibly modified later, that is a generic understanding of physical and cultural features (e.g. hairstyles, dress code, and attributes like specific weapons) that were used to construct Nubian identity in Egyptian art, through which we mostly know “Nubians”.

Of course, there was no clear ethnic border between Egypt and Nubia and southern Egypt was inhabited by both ethnic groups. The best-known case of a double ethnic community is Gebelein, where numerous stelae elucidate the ethnic composition of the local elite. There are ca. 32 such tombstones, and at least 11 of them are showing Nubians. The ethnic identity of the other 5 is debatable. The other 16 seem to be Egyptians. Since only the prominent community members could afford such objects this gives us a hint of the proportions of the ethnic structure of the local elite. Nubians were an important part of it since they constituted about one-third of the depicted elite members or more. The word “about” refers here not only to the number but also to the fact that they are not always “pure” Nubians or Egyptians. Some people had Nubian and Egyptian ancestors.

Physical anthropology analyses performed so far on skeletal remains from Gebelein and elsewhere in the Nile valley aimed at defining differences between Egyptian and Nubian populations. This will be the subject of critical analysis within this project. Genetic data are very desirable but are lacking. Also, there are no sufficient data from settlements to compare the way of everyday life of Egyptians and Nubians in Egypt.

Therefore, we are limited to a restricted number of texts and depictions from a funerary context that may inform us how Nubians saw themselves. The circumstances of making and authorship is of course debatable. Nevertheless, this may help to balance Egyptian sources, prevailing in academic discourse, from potentially Nubian ones.

The case study of Gebelein will be set in a wider context of Nubian presence in Egypt in the 3rd millennium BCE. The material culture, textual, and pictorial evidence dating to Upper Egypt from ca. 3500 to ca. 1800 will be studied. There are depictions and burials of Nubians, for example in Thebes (e.g. paintings in the tomb of General Intef at Assasif from the times of Mentuhotep II and burials of Nubian wives of this king), Kom Ombo (paintings in the burial chamber of Sobekhotep, 12th Dynasty), Hierakonpolis (C-group Cemetery, FIP and MK), and Aswan region (tomb of Setka, late OK or FIP, a bowl from the tomb 206 with a hunting scene at the Egyptian Museum of the University of Bonn). The area surveyed by the Borderscape Project and Aswan-Kom Ombo Archaeological Project provides valuable evidence on Nubians in Egypt in the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE, to name the best-known examples. However, only the Period of Regions / First Intermediate Period (22nd and 21st centuries BCE) offers enough evidence to draw more specific conclusions since it was the time of the flourishing of provincial centres, allowing the development of uncanonical ways of expressing identity. Of course, as usual in the case of Ancient Egypt, the evidence is mostly limited to the burial customs of the elite. Gebelein offers numerous sources, unavailable in such diversity and abundance elsewhere in Egypt. Therefore, it will serve as a case study.

Unexplored so far topics in Egyptian archaeology: 1) double ethnicity and 2) the question, of did Egyptians were “Nubianizing” will be of special interest. The latter is crucial since the so far prevailing paradigm was that the Nubians were Egyptianizing. Nobody was looking for evidence in the opposite direction. Furthermore, the issue of ethnicity is complex in this case. Since Nubians of both sexes were inhabiting the Gebelein region and had children with Egyptians there must have been offspring of mixed descent. Thus, what was its ethnicity? Double ethnicity seems to be exhibited in some cases. The tomb of the Nomarch Ini I from Gebelein, dating to the Period of Regions / First Intermediate Period, will be examined as this case may show Egyptian and non-Egyptian cultural markers. His undisturbed burial chamber was discovered by Museo Egizio’s expedition in 1911, but it was never fully published. A cowhide upon which a statue of the nomarch was placed is a unique case, perhaps alluding to a tradition among the contemporary elite members of Nubian and/or Kerman societies, who buried their dead in cattle skins. Regarding the funerary statue of Ini, his skin was painted red, as usual for depictions of Egyptian men, however, its upper half was additionally painted with a layer of black paint, perhaps to make him look like a Nubian, while the lower part was left red to indicate Egyptian ancestry. In Egyptian art, dark-red or brown complexion was a marker for Egyptian males while black was for Nubians and Libyans.

Thus, the project aims to establish the nature of the Nubian presence, ways of expressing Nubian identity in Egypt and how both groups were interacting in the example of Gebelein. The tomb of Ini will be a case study on the potential expression of perhaps double ethnicity through tomb furnishing and iconography.

Assistant Professor

Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures

Polish Academy of Sciences

Postdoctoral Researcher

Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Anthropology, Department of Egyptology

Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn

Wojtek.ejsmond@wp.pl

3.011

Brühler Straße 7

53119 Bonn

Kontakt

Ludwig Morenz